"Were you in the vax group or the placebo?" It sounds like a simple question, that should have a simple answer, right? And usually it does. Unless it doesn’t. Welcome to the world of the cross-over trial!

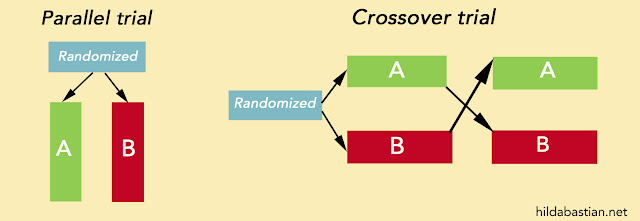

The garden variety randomized trial is a parallel or concurrent trial: people get randomized to one of 2 or more groups, and they continue on their parallel tracks, at the same time. At the end of it, if all goes well, you have solid answers to the main question or questions you set out to resolve.

In a cross-over trial, on the other hand, people start off in one group, then along the way, each group of people swaps over with those in another group. Everyone gets the same options, they are just randomized to going through them in a different order – intervention A then B, or intervention B then A. That’s how the guy in the cartoon can be in both the vaccine and the placebo group.

Let's start with the advantage of doing trials like this. A crossover trial means each person is their own control. With that one move, you have removed a common reason for differences in outcomes – individuals' differences. And that means you need fewer people to get an answer.

Every health intervention question can't be answered this way of course – think surgery versus antibiotics for appendicitis, for example, or a drug that isn't going to leave your body to revert back to your usual state during the break between interventions ("wash-out period").

But what about our guy in a vaccine trial, though? They don't fit this picture, do they? Vaccines may wash out, but the benefits to your immune system of recognizing its enemy sure isn't supposed to!

Crossover trials for vaccines are in the spotlight because they're being used for Covid-19 vaccine trials. I discuss this in depth over at Absolutely Maybe – and for more technical discussion on this, see this preprint on the thinking behind the proposal, and Steve Goodman's slides for the US Food and Drug Administration's deliberations.

The crossover extensions of the Covid vaccine trials can't do everything a randomized controlled trial can do, but they can provide valuable data on some issues, especially if the people stay blinded. High amongst those is how long immunity lasts. That's because you now have one group that was vaccinated early, and one group who had deferred vaccination. After the crossover, if the infection rate between the groups stays the same, you know the early-vaccinated group's immunity isn't waning.

Back to the average crossover trial, though, which will be of treatments. What should look out for with those?

One problem is if the groups before the crossover are treated as though they are parallel trials. That's risky. Randomizing enough people to a parallel trial means you don't have to worry about differences between the individuals skewing the results – you don't have that when you're randomizing the order of interventions, not the people.

You also have to keep in mind what possible influence could the previous intervention have had. If the trial goes on for a while, then you have to consider whether the different time periods are now a factor – and more people might have dropped out before they had the second intervention, too.

And 2 final bonus points: "N of 1" trials are cross-overs. That's when you are trying out treatments in a formally structured way, though like all cross-over trials, it only works in some situations. (A quick look at those here at Statistically Funny.) And there's another kind of trial where people are controls for themselves: (Here's my quick look at those.)

😍😍

ReplyDelete